Perhaps no film genre is as neglected in

the 21st century as the musical. With rare exception, the only

offerings we get are the occasional Disney film, the occasional remake of a

Disney film, and adaptations of Broadway stage shows. When we are graced

with a proper musical film, the demand is high among musical fans for optimum

musical performance, and when a musical film doesn’t deliver this, these fans

are unforgiving.

From the moment talking was introduced in cinema, the musical film has been a gathering place where vocal demigods assemble in kaleidoscopic dance numbers in a whirl of cinematic ecstasy too fantastical for this world. What motivation, then, could Tom Hooper possibly have for tethering this landmark of modern musical fandom in grounded, dirty reality?

The cost was the kind of musical prowess fans were

demanding from a film adaptation of one of the most influential musical stage

shows in history. “Who cares if Anne can sob in perfect rhythm?

Listen to Lea Salonga’s performance—that’s how it’s supposed to sound!” For

some, Hooper had bought his authentic performances at the expense of the most

important musical ingredient.

I'd be remiss not to acknowledge that there are things that I miss about a more traditional method of musicalness. It's every actor's impulse in this movie to sing their lines as they would in a musical, only to sort of peter out with the last word or two of a line, or the last line of a long musical soliloquy, like they've run out of breath. And even actors with musicals under their belt--Jackman, Seyfried, Barks, etc.--elect to take this approach.

And this decision to build the structure of the music solely around what the actor is feeling in any random take means the performers are free to play fast and loose with the tempo or the rhythm. I think this works really well with certain solo numbers like On My Own, but it makes some of the larger group numbers feel a wee discordant.

There were definitely fruits the film had to choose to leave behind in order to get what they wanted. And these are no doubt the same things that critics of this adaptation are bemoaning when they pushback against it.

|

| Camelot (1967) |

But the criticism can also lack a certain nuance, a curiosity for what might have motivated Hooper to play the music this way--because I don't think it's as straightforward as Hollywood trying to dumb down the musical. And moreover, I don't think that Hooper's experiment actually flopped. This is genuinely one of my favorite musicals on the books.

While I certainly think there’s something to the complaints against the film adaptation of Les Miserables,

especially as they pertain to issues with the larger genre, they aren’t quite applicable

to Hooper's film. (Well, not this film. We'll save Cats for a different day.) Far from stifling the magic of

movie musicals, Tom Hooper’s adaptation of Les Miserables deconstructs the purpose of musical

numbers in a film and creates something that fans of the musical should find

validating.

Stylization

vs Naturalism

So let's start by agreeing that film can serve any number of purposes. Some films are here to thrill, some to comfort, some to sober. Let's also decide that film has a variety of tools and techniques by which a film might express the ideas it chooses to convey its meaning. The proximity between the camera and the subject, the choice of how close you want the audience to character at any given point, is one of many decisions a director gets to make.

And for the sake of simplicity, let's decide that a filmmaker can broadly approach their film in one of two ways: they can go stylization, or they can try their hand at naturalism. (These are not like the standard terms, by the by. Some prefer theatrical vs organic or whatnot. The names are fluid, the principles are universal.)

A film

that behaves naturalistically will try its best to imitate real life and will

resist avoid breaking the illusion of reality. A film that behaves

stylistically does not care for realism and relishes in decorating itself for

the audience’s pleasure.

Neither form is necessarily better

than the other, both just elicit different responses from the audience, and it’s

important for the filmmakers to be mindful of how they employ either form of

storytelling. These two ideas also exist as ends on a continuum, and while most films fall on one side of the divide, a movie can place itself anywhere along the spectrum to accomplish what the director intends.

|

| Saving Private Ryan (1998) |

This is funny because if there’s one genre

where stylization ought to be the default, it’s the musical. There's nothing really natural about a person spontaneously bursting into song. The audience will only accept this storytelling device

if the storytellers somehow modify the reality they’re presenting to the

audience, usually to make it more fantastical. Audiences generally

don’t, for example, take exception when characters in an animated fairy-tale start to sing.

Hence, musicals almost always go for stylization over naturalism.

|

| It's raining stylization in Moulin Rouge! |

We see this in the film’s boisterous musical numbers,

theatrical acting, and explosive color. This aggressive stylization is a deliberate choice made by a

director who knows what emotional response he wants to elicit from his viewers

and how to achieve it. A film can go the exact opposite way and root itself in

dirty, familiar reality if that’s what the director is intending, but because musicals

only seem to work in an elevated fantasy-like world, they favor stylization. From here, we can already start to see the

risks Hooper took with his adaptation. Musicals are so dependent on a suspension

of disbelief that naturalistic movies don’t offer, and yet, it leans hard into naturalism.

And that’s the most interesting question posed by Hooper’s film: is stylization the only route for movie musicals? With some tinkering, can a naturalistic movie musical work?

And that’s the most interesting question posed by Hooper’s film: is stylization the only route for movie musicals? With some tinkering, can a naturalistic movie musical work?

Some musicals have tried. The film adaptations of both Cabaret and Chicago are notable for making room for musical expression within a grounded, realistic world. Cabaret manages this by reworking all of the stage show's musical numbers into actual stage numbers performed in-universe on a stage with an audience, as it is in real life. In Chicago all of the musical numbers (save for the first and last which are in-universe performed on stage) are clearly designated as fantasies that take place in the head of our protagonist. Both film adaptations integrate music and song with a gritty reality by using the artifice of performance or imagination.

But Les Miserables isn't playing that game. The music isn't mediated by some artificial interface. The music is happening in universe without a rainbow in sight. It's not the standard approach for movie musicals, but Les Miserables isn't a standard stage musical.

A Song of Gunfire and Dirt

It is worth noting

that the Les Miserables is not as opulent as the standard Broadway show, at least not in the same way as something like Beauty and the Beast. You won’t find a lot of ensemble dance numbers in "Les

Mis." Compared to other juggernaut musicals, Les Miserables doesn’t rely

a lot on presentationalism.

By contrast, something like Wicked exists in the

zany, colorful world of Oz complete with flying broomsticks and talking

animals. Phantom of the Opera takes place in the world we know, but it

is still set in a stately opera house menaced by a near-supernatural musical

madman. As such, it benefits from the elevated storytelling of musicality. The

subject matter of these shows naturally lends itself to the larger than life

devices of stylistic storytelling.

By contrast, something like Wicked exists in the

zany, colorful world of Oz complete with flying broomsticks and talking

animals. Phantom of the Opera takes place in the world we know, but it

is still set in a stately opera house menaced by a near-supernatural musical

madman. As such, it benefits from the elevated storytelling of musicality. The

subject matter of these shows naturally lends itself to the larger than life

devices of stylistic storytelling.

On the other hand, Les Miserables

tells a story of war, poverty, prostitution, and general misery. "Les Mis" doesn’t try to lift its audience from the grunge of reality the way the other

shows do: it reminds its audience incessantly that reality is dirty and cruel. The show

really isn’t even about overcoming the despair of real life (the weaselly Thernardiers

survive and while all the hopeful rebels get blown to bits) as much as it is

about the potential to be a good person even in a world that is cruel and

unforgiving.

These characters don’t sing to celebrate the fancy chandelier hanging above the audience: they sing because their grief and agony can’t be properly expressed in spoken dialogue. Eschewing the expected glass-like atmosphere of the standard musical in favor of something more raw and soiled might not have been as crazy as it sounded on paper.

This adaptation draws less from something like The King and I or even something like Oliver! Its primary inspirations derive more from something like the neo-realist movements that arose around the world in the wake of WWII.

|

But these were films that captured a sect of humanity that was forgotten and aching in the wake of such devastation as two world wars. Seventy years later, these two rivers meet in a big-budget musical such as Les Miserables whose primary concern is a people who are discarded by the society they live under.

Is that the only route Hooper could have

gone? Probably not. But I would dare to say that the filmmakers would be faced with at least as many hurdles if they had tried to approach this musical about war and prostitution with a My Fair Lady outlook. But it’s not hard to imagine that a filmmaker would see view the

stage play and imagine what it would be like if instead of using music to

paint over the characters’ suffering, a film adaptation used the music to

embrace the suffering.

But the real centerpiece is, of course, Anne Hathaway and her Oscar-winning performance as demonstrated in her iconic rendition of "I Dreamed a Dream." We’ll discuss at length what the singing style contributes to the song, but for

now let’s draw our attention to the other facets of her acting: The wear of her

voice. The way her eyes at the start appear so lifeless only to flare at the

song’s climax. Her hyperventilating sobs, almost like she’s lost control of the

performance. Hathaway isn’t just singing about being beaten, she’s singing

while beaten.

The bulk of this song is presented in a

single, close-up shot. Refraining from excessive cutting allows Hathaway to

control the scene as the audience has the time to absorb her performance. All

the while, the camera drifts aimlessly—slightly, but noticeably—like it’s

fighting the need to succumb to exhaustion and sleep.

The creative team was also mindful of

Anne’s appearance. Note the tattered dress threatening to slip right off of her

thin frame and the thick coat of dirt on her face: her battered image reflects both

Hathaway’s performance and Fantine’s crippled psyche.

The creative team was also mindful of

Anne’s appearance. Note the tattered dress threatening to slip right off of her

thin frame and the thick coat of dirt on her face: her battered image reflects both

Hathaway’s performance and Fantine’s crippled psyche. Did Hatheway get that Oscar just because she knew how to cry while singing? Or is it because there's something just astounding about the way her voice springs such life into this dirty scene all while her corpse-like eyes just stare blankly? Is it in the way that we see how the sincerest baring of the soul, even its ugly parts, can be enough to resurrect the soul?

Here we see Hooper utilizing his

full set of tools to craft the scene in all its despair and agony. From this we

see, first, that there is more that goes into developing a scene than just the

singer’s ability, and second, that Hooper overlooked nothing when building his

naturalistic musical. This is a face of the music that cannot show itself in its cradle on the stage. The possibilities are a little too enticing to leave unexplored.

The common thought is that qualified

Broadway performers are either too expensive for movie musicals or they lack

the star power to draw audiences, and so the roles are often given to A-list

celebrities who have never been in a recording studio. Why cast a trained

singer for Belle when tumblr has been fantasizing about Hermione taking the

role since the late-middle ages? The results are often disappointing.

It’s easy

to lump Hooper’s film in with the rest of the

musicals-that-wish-they-weren’t-musicals, but that assumes that the intent and execution are the same across each film. 2017’s

Beauty and the Beast cast a novice singer in the lead because the draw of Emma Watson apparently compensated for the Broadway prowess a fairy-tale princess like Belle deserved, but I digress ... Les

Miserables plays a similar game, but here it actually reinforces the text’s exploration of the powerlessness

of the human condition.

Russell Crowe in particular has kind of become the butt of these jokes. But I really like his interpretation of Stars, which I also much prefer in this film as the demarcation between the two major timelines. I wouldn't call this performance tender or soft, but I think Crowe recognizes that, even for someone like Javert, music is a sort of safe space to let all sorts of insecurities and fears bubble to the top.

The vocal prowess of the singer is just another tool that can be used

to further the naturalism or stylization of the film. After all, part of

musical escapism comes from the bliss of hearing musical numbers performed to

perfection: The hills aren’t just alive with the sound of music, they’re alive

with the heavenly tones of Julie Andrews. In a movie like The Sound of Music,

the style of the vocal performance is suited for the response they are aiming

for: bliss and optimism.

But what if the world we’re creating is

neither blissful nor optimistic? What if it doesn’t have that safeguard that

guarantees happy endings and perfect pitch? What if the characters aren’t angels

of music but just ordinary people struggling to get by? As dearly as we may

have wanted Hugh Jackman to replicate Colm Wilkinson’s pounding rendition of

Valjean’s Soliloquy, there is something very humanizing about the

breathlessness of Jackman’s portrayal in the movie.

One could argue that this attempt at

capturing the voice of the commonfolk is undermined by the casting of Hollywood

royalty, and there’s something to that. I think there could have been a fascinating finished product if this film had tried a neorealist approach and cast non-famous faces to fill the roles of the lonely and forgotten. That was never going to happen in this economy.

One could argue that this attempt at

capturing the voice of the commonfolk is undermined by the casting of Hollywood

royalty, and there’s something to that. I think there could have been a fascinating finished product if this film had tried a neorealist approach and cast non-famous faces to fill the roles of the lonely and forgotten. That was never going to happen in this economy. But I also don't think the effect is totally lost by casting established names. This film is one of those rare instances in which the make-up is

done to make the actor look less appealing, and the effects are clear.

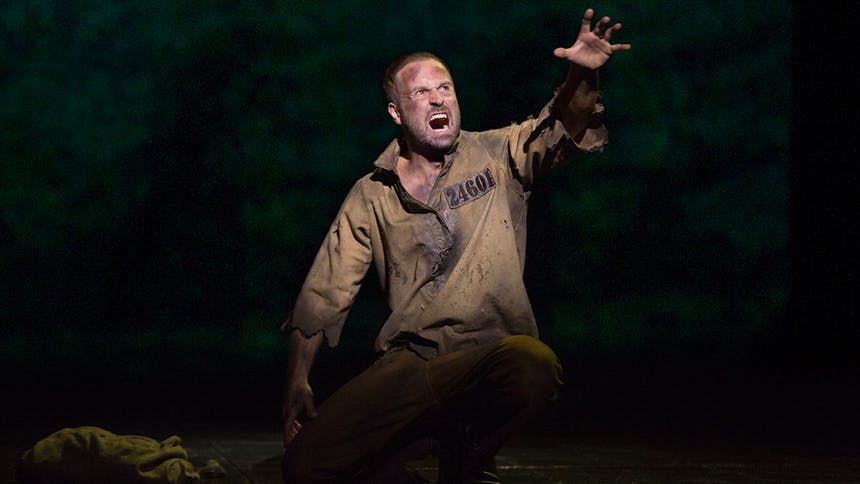

It says a lot about this film and its commitment to a starved aesthetic that

even a stud like Hugh Jackman looks like he’s fresh out of Azkaban.

Hooper’s method of directing plays right

into the strengths of the film medium. The grandiosity of stage performance

couldn’t possibly fit into the frame of the camera, but the intimacy of the

close-up lends itself to the fine texture afforded by a weathered, beaten

performance. The fact that even those of the cast that are stage actors like

Samantha Barks of Aaron Tveit still sing naturalistically has me thinking that

this style was a deliberate choice, not just a limit of the cast’s ability.

Consider how this approach

complements a scene like "A Little Fall of Rain." Eponine is dying in the arms of the man who never loved

her back: the scene is ripe for poetic musical expression. At the same time, her

life is fast fading: Samantha Barks’ performance should reflect the frailty and

near lifelessness of her character. Hooper’s execution of the scene is able to reconcile

the conflicting demands of musicality by using song to spotlight the pain of

the characters rather than hiding it.

One of the running critiques of the musical as a genre has been the way it sanitizes the nasty reality for the viewer, almost creating a state of dissociation for the audience by allowing them to opt out of the parts of life that are agonizing. And when the stage musical premiered in 1985, a sizeable number of critics were straight-up repulsed by the project for watering down classic literature with singing. Michael Billington wrote of the stage show back in 2010,

"What irked some of us back in 1985 was the claim by the original directors, Trevor Nunn and John Caird, that we were watching a piece of High Seriousness that required the resources of the RSC to stage. You could also argue, as I would, that Les Mis, by ditching spoken dialogue in favour of a through-composed score, led the musical down a false trail: away from the fun of wit, satire and romance towards the pomposities of pop-opera."

|

I think one of the reasons why Les Miserables the stage musical resonates with people is that, despite this baseline, it understands that the experience of occupying such a world is actually a conduit into some very powerful human experiences and insights that can only be properly captured through song. And so for a musical that captures this paradox so unflinchingly, there is something powerful to a film adaptation carrying all that--not just by translating the story, but in using all the nuances of film language to impart the dialectical freefall that comes when you bring hope and despair together.

Yes, this fusion may create some initial dissonance. Like, where is this music coming from? But I think the film also ultimately leaves it in the hands of the viewer to choose whether to accept it, and the payoffs for making the jump are significant.

At

the End of the Day . . .

The musical’s relationship with reality

has been investigated for decades, and they've been asking us to make leaps all the while. The earliest musicals weren’t the kind where

a character would be walking down the street and suddenly burst into song only

to have the townsfolk burst into that same song, or where the leading lady

would sit down by her window and sing her feelings to the birds—that would have

looked really weird to film’s earliest audiences.

In movies like The Gold

Diggers of 1933 or Going Hollywood, the songs were rooted in a real-life

context. The characters, usually radio or stage stars, would break out into

song only on a stage in front of an audience, just as they do in real life. To these

audiences, a musical meant a film like A Star is Born more than a film like The

Greatest Showman. The introspective, spontaneous character number like “Over

the Rainbow” didn’t emerge until the genre had dabbled in fantasy-style films

like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves or The Wizard of Oz and the

possibilities of musical expression were really unshackled.

And I guess that's kind of the crux of what really makes me fond of this movie. It takes me back to like the early, early days of musical-ness when filmmakers and audiences were still figuring out what the musical could be and how you made that machine work. And the state of musicals in the 21st century was so dry that we were basically starting over from scratch. The seed that seemed to spawn this whole experiment was this idea that even when a person feels their least dignified--when all they have to offer is their own voice, however broken--the human soul retains its beauty, the kind that is absolutely worthy to be expressed through melody and lyric.

Filmmaking has always been about experimenting.

It’s when a storyteller wonders “what would happen if . . .” that boundaries get

broken and both the filmmaker and the audience gets to discover something new. Again, sometimes experiments fail and we can have discussions about those too, but those conversations should always be accompanied by curiosity and interest.

This is a film that believes singing doesn't just belong in a plastic fantasy world. This is a film that imagines what it would be like if the human spirit within us all, the part of us that transcends the dusty naturalistic world we live in and so desperately wants to break out of it, could find its way into the spotlight for once. And I think it's fine if we decide to welcome that.

--The Professor

--The Professor

_____________

I felt compelled to revisit this film and this piece in the wake of a lot of developments in the musical world. It was after this piece went live that Hollywood actually put out a fair number of movie musicals with varying approaches. I came back to this movie after the reverie of the Wicked film adaptations (and coincidentally, after finishing Victor Hugo's original novel for the first time).

And about six years of musical movies later, I can see how a number of these films germinated from many of the same ideas present in Hooper's "Les Mis," but they took different routes to get there. Something like Spielberg's West Side Story aims for a very similar earthy and broken aesthetic, but it achieves this without compromising the inherent lyricism of the material. And the "Wicked" films were able to tap into the spontaneity of live-singing without compromising the sheer vocal majesty promised by the formidable songbook.

And so I was worried that coming back to this movie would be an exercise in embarrassment. A reminder that I bet my inheritance on the wrong horse. "What have I done signing my name to this movie?"

But even with some time away from the film, and with other avenues of musicality open to my eyes, I still found myself very moved by this movie's synergy. I still agree with the thesis of this piece, that the movie's backdoor approach to musicality works really well within this specific vessel.

I'm personally grateful that musicals have on the whole taken after The Greatest Showman versus Les Miserables because I don't think that the Les Miserables approach works for most musicals--as we found out the hard way with Hooper's own interpretation of Cats. (And ... no, we're not going to let him live that one down for a long, long time.)

But I'm also grateful for the conversations this movie started. The movie was enough of a hit with audiences and The Academy to keep the door open for more musicals. I see in this movie the musical genre stirring, awakening, rediscovering itself. And for that, I have to be at least a little grateful.

Would you say Singing In The Rain is a stylized or naturalized film?

ReplyDeleteI'd say stylized in the same way most musicals are stylized. Singin' in the Rain is very dependent on both the precision of performances by stars like Gene Kelly and the general "shininess" of the colorful ensemble dances and such.

Delete